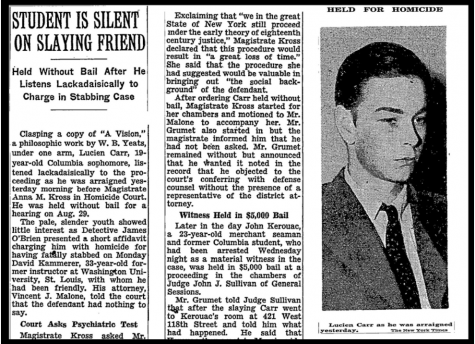

On August 14, 1944, Lucien Carr killed a man. He stabbed him twice in the chest with a pocket knife, bound his limbs, and rolled him into the Hudson River drunk and, perhaps, very close to losing his mind. It’s quite simple to end that story as it’s told–quite easy to never elaborate, to hush at the name and close the book, silently cursing Columbia’s old library for not saving him–but the story will never, truly, be told how it’s meant to–by Carr himself.

Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and William S. Burroughs are names that will always bounce around English majors’ notes, classics in every sense of the word–idolized, ached for, memorized, and copied–they were principles of a literary movement, and they were called, and modernly referred to, as the Beats generation. But they would not have existed without Lucien Carr, 19 at the time, a pupil who studied with them at Columbia University in New York.

He was said to be admired by all, and endlessly handsome, well-spoken, and charismatic, but perhaps above all, was the “glue” that brought the Beats together, as Ginsberg himself had said. He had a reputation around campus for being a literary mogul, Kerouac even describing him as “Shakespeare reborn” in Vanity of Duluoz. He was individually interesting to each man, and while they all remained very close friends throughout the years and until their deaths, it was no secret that Carr had always been the center.

David Kammerer was considered to be Carr’s mentor, as much his God as he was his Lucifer, and taught Carr a lot of what he knew. Kammerer was his guidance counselor, his literary flashlight–but Carr was not just his student, rather his deep obsession, who he followed to Columbia, whom he stalked, and who he wanted a sexual relationship with. Carr, however, was obstinately straight, even dating a girl from Barnard University nearby.

On the night of August 14, Kammerer followed Carr to a park in the West End, and they drank until 2 in the morning. As they laid on the grass, Krammerer made a comment described by the New York Times as an “offensive proposal,” and Carr had supposedly refused adamantly, and, after a fight of which Carr was losing, Carr killed him with a folding knife.

He walked to Burroughs apartment in Greenwich Village, and then to Kerouac’s, admitting that he had finally “disposed of the old man,” the night before. David Krajicek of Columbia Magazine called the next events a, “macabre walk through Manhattan,” in which they buried Krammerer’s reading glasses, Carr’s pocket knife, saw a film, and went to the Museum of Modern Art. The next day, Carr confessed, a copy of W.B Yeats’ A Vision tucked securely under his arm as he did so.

The following day, Burroughs and Kerouac were arrested as accessories. Burroughs was quickly bailed out, but Kerouac’s family had refused, and so his then-girlfriend, Edie Parker, bailed him out after agreeing to marry him as requested by the judge before she did.

Ginsberg was in love with Carr, intensely so, and was the only one who had avoided arrest, and who had, perhaps, been most affected by the events. Ginsberg spent weeks alone, mourning the assumed end to both of his friends.

Carr, however, got away with second-degree murder, as the court deemed him “mentally unstable, but not insane,” and called the killing of a homosexual predator an, “honor slaying.” It is deeply disappointing, especially because Ginsberg, a famously out gay man, became such a beacon for queer youth in literacy. Nonetheless, Columbia quickly came to Carr’s defense, despite the fact that all of the Beats were consistently hesitant about traditional education. Columbia became a driving antagonistic force in a lot of Carr’s New Vision, which was later carried out by Ginsberg and the other Beats.

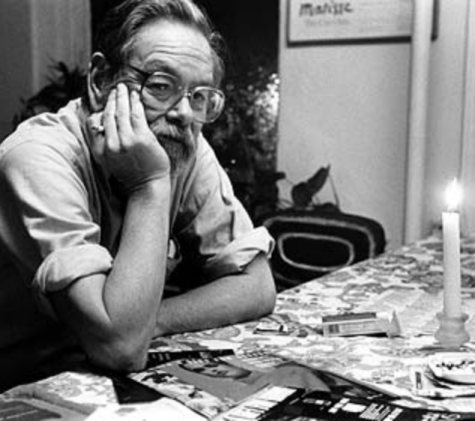

Carr spent eighteen months in a gentle facility, and he came out of it with a few rough moments but led a mostly obscure life. He became a wire-service newsman with United Press, and later United Press International. The Beats stayed in touch throughout their lives, their conversations documented in letters that can be found in Columbia’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

He did not want to be associated with Kammerer and his past, and even asked for his name to be taken out of the dedication in Ginsberg’s Howl. But it’s important to note that Carr was not Kammerer, and not what happened to him, and certainly not what he did–he was a good man, perhaps roughed up by a cold world completely unaccepting of anything to do with homosexual activities, and anything to do with broken, snobbish artists whose legacy would become something of a cautionary tale–but Carr, I say proudly, is a literary icon to myself and others, and his work in bringing the Beats together means more than perhaps the New Vision itself–he redefined literature, from the sidelines or otherwise, and should be thanked for it–over and over, until people know the man behind the August 14 in which changed his life.

A former UPI colleague of Carr’s, Wilburn Hampton, wrote a fitting epitaph for Carr following his death in 2005 for the Times. He called Carr, the man behind a revolution of poetry, and a previously handsome, alluring young man, “a literary lion that never roared.”

And made him, forevermore, the saddest story never told about the greatest writer that never was.